1 What is Data Science?

Updated for S2026? Yes.

While the term “Data Science” has been around for decades, the notion of “Data Scientist” as a profession has it’s origins in the late aughts, when data analysts at LinkedIn and Facebook wanted a better descriptor of the work they were doing. They weren’t statisticians, and they weren’t engineers, they were a (secret) third thing. So they made up a phrase: Data Scientist.

We can think about this secret third thing about containing three, overlapping set of skills

- Domain knowledge in the area you are working;

- Computational knowledge to literally process inputs and produce outputs.

- Statistical knowledge to guide decisions and to interpret findings.

We can think about this as the Data Scientist three legged stool. You need all three of these things in order to succeed as a data scientist.

This class will primarily focus on the second thing, gaining the technical ability to use R to organize, process, and interpret data. But I also want you to know that this is wholly inadequate if you actually want to do data science.

You will need domain knowledge, which is simply a deep knowledge of the substantive area you are working. in. This is something that you will gain in your time at Penn and in the workforce.

You will also need knowledge of statistics. We are going to talk next week about why this class is not a statistics class, and what specific framework of thinking you need to take in order to interpret data correctly. This can be gained in additional coursework (like PSCI 1801, or a similar statistics or economics course).

My work at NBC is a good example of how these three things come together. I (and our team more broadly!) have the technical ability to write code that takes raw election returns and produces models. The models I choose and the way that I interpret them are guided by my years of experience in political science. My ability to form conclusions based on the data I am seeing is based on my knowledge of mathematical statistics. All three of these things have to work in concert for me to be a good analyst. I would be really lousy if all I knew how to do was to write code.

That is the technical definition of being a data scientist, but I want to think about a more nuanced but important definition.

“Data Science” is a profession. Like all professions, is it defined by trust and accountability. Whether accounting, medicine, engineering, or skilled trades: the uniting feature of these things is that there is a collective promise that the profession has built modes of training and accountability such that you can trust that the work will be done competently. Now, for these other professions there are literal professional organizations that regulate training and generate sanctions. We don’t have that as data scientists (other than being shamed on Twitter for bad analysis), but we still want to project an image of honesty, transparency, and accountability.

So, more broadly, becoming a data scientist is committing yourself to a profession that has norms of accountability, and producing work that you and other people can trust.

How can we get there?

1.1 Some cautionary tales

Well here’s how you don’t get there.

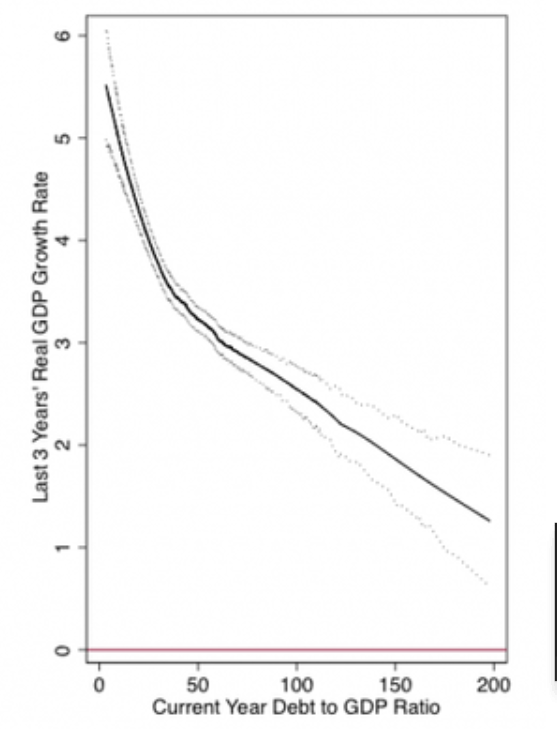

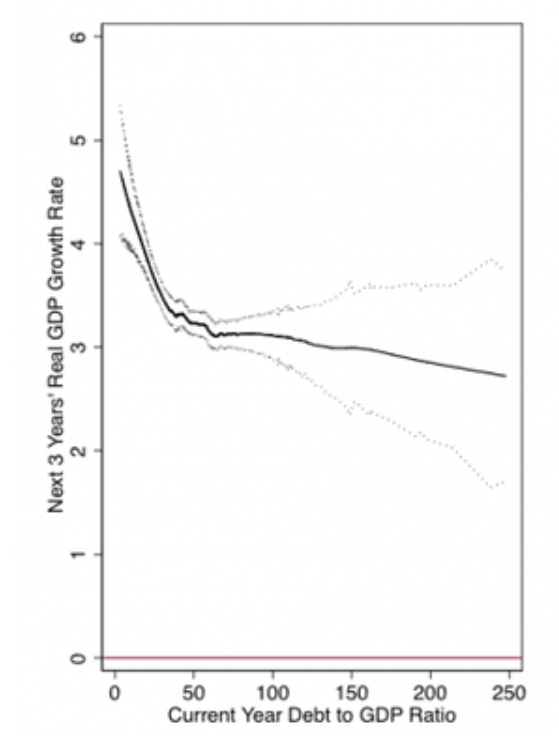

In 2010 Economists Carmen Reinhardt and Ken Rogoff published a paper in the American Economic Review detailing the relationship between the amount of debt a county had and their growth in GDP. Critically, they found that there was a profoundly negative relationship between these two things, as the figure below shows. This finding was used widely by central economic authorities in the aftermath of the financial crisis to push low-debt austerity measures.

Another team of Economists were skeptical of these findings so they downloaded the same data and re-ran the analyses in the paper. This is what they found:

Uhhhhhh pretty much nothing….

So what happened here? In short, the original authors were using Excel and made a few bone-headed coding errors. One of the errors they made was that they didn’t drag a formula all the way to the bottom of a column. Because of this, a good chunk of the data simply was left out of their analysis.

If you are more into the natural sciences, how about this: 30% of published papers on genetics are wrong because the authors use Excel. The errors here are due to Excel’s over-zealous conversion of numbers into dates and scientific notation. An actual genetic marker is “SEPT7” which, of course, Excel converts to September 7th. Another maker is “2310009E13” which Excel converts to “2.31E+13”.

One more example: in September 2020 England failed to report approximately 16,000 COVID-19 cases. The culprit, again, was Excel. The public health authorities were using the outdated .xls format in R which has a row limit of approximately 65k. Once the cases got over that number the spreadsheet was no longer able to be updated.

Now, it’s not a coincidence that all of these mistakes involve Microsoft Excel. However, the lesson here is not simply “Do not use Excel” (though, you shouldn’t).

Instead, the lesson here is that to be a professional data scientist who produces work you can stand behind you need a system that is robust to making mistakes. Making mistakes is an unavoidable part of being human. Indeed, Neils Bohr said, “An expert is someone who is made all possible mistakes in a narrow field.” What we need to do, then, is to have a system that allows us to catch and correct our mistakes so we don’t end up in a list like the above.

How you accomplish something like this is the same way you get anywhere: practice! But we can also think about some general principles and practices that gives us a higher degree of accountability. To help accomplish this we are going to use R in a fundamentally different way than you use Excel.

If I was working with data into Excel, I would load it in, make a bunch of changes – maybe reformatting some variables, calculating new variables, choosing variables to put into a regression – and then I would save what I have done so I can pick back up on that work the next time I sit down at my computer. But critically, I will have no record of exactly what I did the last time I worked, I just have this new, altered, dataset to work with.

In R (and many other programming languages) instead of constantly saving our data and output, we instead save a script that tells us all the steps we need to take to go from our raw data inputs to our polished final outputs. Because each step of the process is recorded, we can review those steps to find potential mistakes. More importantly, we can un-do those mistakes by just changing a couple of lines. We also never have to worry about making un-reversible changes because we accidentally saved the wrong version of the dataset.

For what it’s worth R&R deflected criticism, never admitted to anything, and kept making the same arguments even though their data didn’t support them. At least one genetics researcher interviewed about problems in that field said that she doesn’t have time to learn R, and that the quirks of Excel is “One of those things that I just accept.”

Both truly unhinged responses.

1.1.1 The Three Rs of Good Coding

Broadening out, I think about there being “Three Rs” to good data science coding that help us to trust our work and that allow for accountability.

- Replicable

Can someone (or more likely, you in the future) understand what you’ve done and do it themselves? The way that we meet this goal is to write well formatted scripts that give a full record of what we did from raw data to output. Additionally, we make comments in our code to make clear the decisions we are making so that people in the future are clear about what we did. Good comments indicate intent, not mechanics.

- Reversible

Everything that happens between downloading a data set from the internet to producing a figure needs to be documented. And we should always start from that raw data input (that never gets changed). We never do any pre-processing in Excel. “But it would be so easy to go in an delete that header that we aren’t using”. No! The potential of making a mistake you can’t find later is too high. These steps together make our code reversible. We can always go back to the start and re-run our script to the point we made a mistake and to undo it.

- Retrievable

To do any work as a data scientist you must understand the file system on your computer. You must know where you have stored things and be able to find those scripts and data when you need to. You should understand folders and sub-folders, and how to organize them in a way that will make sense to other people and to future you.

It has become a bit of an obsession that the current generation of students don’t understand where files are stored on their computers. I have been around universities for a while and there is always some version of “kids these days” so I generally discount any grumbling like this. That being said, the ubiquity and genuinely incredible ability of Spotlight search on Mac has pushed people of your generation to discount the importance of organizing files. It pushes you towards thinking about your computer as a “laundry basket” where you store all your files (maybe on the desktop, maybe in downloads) and then use spotlight to find those files when you need them.

The proper system for serious data work is to use the “nested file drawer” system, where things are organized hierarchically.

On Canvas there is an “Example Final Paper” folder that highlights how this should work.

On my computer this folder is located at

/Users/marctrussler/PORES Dropbox/PORES/PSCI1800/Final Project/Example Final Project

On my Macbook there is a folder for me(marctrussler). In that folder I have saved my dropbox folder. Within that Dropbox Folder are many things, including a shared folder for PORES. In that folder are course notes for many courses, including this one. In that folder I have a specific folder for the final project for that course. In that folder I have an example final paper. In that folder I have specific places to store data. I would tell R that this is the folder I am working out of and it would know where to look for data, or to save figures, or anything else. In the future if I want to reference this final paper I know exactly where to look for it.

Part of my job as a professor is tough love, so here it is: if you want to work in this field you have to understand the file structure on your computer and use it. You will not be taken seriously otherwise. I don’t care that it’s easy to find files with Spotlight. In the final project of this course you will send me a zipped folder that contains your final work, along with all the code and data that produces that final work. If that’s not organized in a proper format (and we will talk about what that format is!) you will receive a signifcant deduction.

Additionally, you will notice that where I am working is out of my dropbox drive. All of the major cloud backups (icloud, dropbox, google drive, box) work by simultaneously storing files both on your physical hard drive and in the cloud. Every time you save a file that is saved in one of these locations it is backed up the cloud automatically. Because everything I do is backed up the cloud, I could walk down to the Schuykill, throw my laptop in, and tomorrow I would be back up and running on all my projects as if nothing had happened. All data science jobs will expect you to do the same. While it’s not a requirement: I’m telling you right now that this is very easy to do. If you come to me in 2 months and tell me that you spilled coffee on your laptop and next an extension, I will refer you back to this paragraph.

These three Rs are the start of how to be a professional with credibility, not the end. They are an important foundation to start building a workflow that will allow you to have trust in your work, and to be able to project that trust to other people.

1.2 What about Chat-GPT?

The elephant in the room for this class is Chat-GPT.

By showing up to this class I am going to take as a start that you believe there is at least some utility to being here and learning this material. Still, it is reasonable for you to sit there and wonder if it’s worth taking an elementary coding class in the age of AI.

Put another way: is this is just a class in learning long division? When I was in elementary school we were taught how to do division without a calculator. Other than the fact that the algorithm of long division makes you practice mental math, it is not helpful to know the algorithm for long division. It has no real benefit beyond the edge case of having to get a precise product without a calculator. Is that what’s happening here?

My answer is a very definitive no. A requirement for you to become a good data scientist is to work through the elementary material without the use of AI assistance. This is despite the fact that Chat-GPT could almost certainly get an A on all of the assignments for this course. What’s more: it is genuinely an insanely helpful tool that I use all the time in my own work!

So why do I believe that it’s important that you go through the hassle of learning do to this stuff without the use of AI? Am I just hazing you?

The reason that using AI to do your work at this stage would be disastrous for your development as a data science is directly related to the major theme of this chapter: that being a professional data science is about producing output that you and other people can trust.

In it, they liken AI tools to (very smart and eager) junior employees:

Using AI well bears resemblance to managing well: just as with human employees, we need to break tasks into small, easy to follow chunks and constantly check output and understanding. We also need to provide all relevant context to these models so they know what our expectations are and what success at any given task looks like.

AI tools are helpful, but not perfect. They make mistakes because they don’t have all the information that we have, and rely to heavily on fitting a merely satisfactory solution to whatever training data it has available to it. It often presents these solutions with a mis-calibrated amount of confidence. This is (no offense) exactly what junior employees are like.

So in order to make use of this very smart and keen employee, you need to have a very clear idea of what you want it to accomplish, a deep understanding of the types of steps that are needed to accomplish that task, and the ability to assess the output to ensure it completed the task successfully, and to manually take over and alter the output if it did not.

When it comes to writing code, you are (right now) completely incapable of performing these overseeing tasks. (Again, no offense. If you knew how to do this you wouldn’t need to be in this class!) You don’t have experience writing code so you don’t really understand the problem solving steps needed in managing data and where pitfalls might be. You don’t really have an ability to assess completed code to know if the results are reasonable and whether the conclusions being drawn are correct. Because you don’t know how to code you absolutely cannot take the output provided by AI and alter it to better fit what it is that you want to do.

It is obvious for something like writing why the use of Chat-GPT is problematic. Writing isn’t just a mechanical exercise, it represents (or it should) the clear and sequential logic of the author. As William Zinnser says: clear writing is clear thinking. The process of writing allows forces us to think more clearly about the information that we have, and to organize it in a way that then allows us to incorporate new information or abstract to new problems.

But coding is just the language of computers. This doesn’t feel like “writing”, but the process of coding similarly forces us to clearly think about a logical sequence of steps to organize what it is that we know. That new scaffolding of organization allows us to incorporate new information or more easily re-purpose what it is that we’ve built into a new purpose. But without the initial work to build that scaffolding (i.e. going through the steps of writing code in order to organize our thoughts) the whole thing breaks down.

In order to get to a place where AI is a helpful tool, you need to learn how to use code to organize data and your insights into actionable material. You’ve got to learn the language.

The second piece of the above linked paper that I liked more directly relates to our big theme of trust:

Analysis work requires a high level of detailed verification to ensure accuracy. Unlike debugging a piece of traditional software, where the main questions might be “does it run” or “does the frontend look like I want”, inaccurate analysis can often look deceptively compelling at first glance. Verifying analysis code involves not just ensuring accuracy of the outputs, but every step along the process. Did the model make the right assumptions when it dropped null entries, recategorized values, or aggregated data? This might involve a tedious, line-by-line review of generated SQL or Python, and the cost-benefit balance of “write it manually” vs. “generate with AI” may start to tip back in favor of the manual route.

If the work that you are doing matters (and I hope that you imagine yourself doing work that matters!) then you simply cannot trust a black-box process to do things right. Again: there are lots of things that AI does well, and it’s tool that I use frequently. But, I have the knowledge and expertise to lookat what it has produced and to make sure that it has done the right thing. For things that really matter, for things that I have to stand up and say “this is right!” then I absolutely, positively, would never use AI. What I am doing is too important, and the stakes are too high, for me to not understand all of the steps of the process and to ensure that they were done correctly.

So: why not AI? Because you are becoming a professional, and professionals produce work that can be trusted.